As part of the book that I am working on, "

Zero to Agile in 90 Days or Less" I decided to include some case studies to illustrate how Agile is different, the problems that people run into and the solutions that they find, as well as the results. One of the companies that I discovered in my search for case studies was Litle & Co. I was immediately struck by their high level of expertise and success with Agile. I couldn't wait to hear how they did it, their trials and tribulations, and I am very grateful to them for allowing me to use them as a case study. The case study speaks for itself, so without further ado...

Case Study: Litle & Co.Litle & Co. is a leading provider of card-not-present transaction processing, payment management and merchant services for businesses that sell directly to consumers through Internet and Multichannel Retail, Direct Response (including print, radio and television) and Online Services. They interface with the world’s major card and alternative payment networks, such as Visa and Master Card, and PayPal, and must be available 24/7 with no downtime.

During the founding of the company in 2001, the initial team of six developers wanted to use Extreme Programming (XP), an Agile development methodology. Some of the developers had used it before and the rest had read about it and liked the ideas. When they talked to Tim Litle, the founder and Chairman, about using Extreme Programming (XP) they told him “you’ll have to accept that we won’t be able to tell you exactly what we will deliver in 9 months.” Tim said, “That’s fine with me, I’ve never gotten that anyway!” He agreed not only to use it, but to insist on it as the company grew and brought in additional management. He liked the idea that he could change his mind about prioritizing feature development for merchants without cancelling or shelving work in progress.

In 2006, Litle & Co. landed at No. 1 on the Inc. 500 list with $34.8 million in 2005 revenue and three-year growth of 5,629.1 percent. In 2007 Inc. magazine cited Litle & Co.’s 2006 revenue as $60.2 million, representing a three-year growth rate of 897.6% over its 2003 revenue of $6.0 million. How has Litle achieved these impressive results? One factor that they cite is their use of Agile development.

Litle uses many of the XP practices including pair programming. The director of software development, David Tarbox, said “at first I thought I would hate pair programming, but I quickly came to enjoy it and depend on it.” Some of the side benefits that they see in pair programming are better on-boarding of new developers due to the mentoring and training that is inherent in pairing. They also like the fact that all code was developed by two people which provides both redundancy for knowledge of all code and real time code review. It may be that one of the developers for a piece of code is on vacation or otherwise unavailable when somebody needs to talk to them, but it is rarely the case that both are.

They started with weekly iterations then moved to 2 weeks then 3 and are now monthly. They gravitated to a month because it was the easiest cadence for everybody to work with and it meant that the whole company was able to adopt that same cadence. Agile development is part of the psyche of the whole organization. It permeates every aspect of the organization.

One thing that other areas of the organization had to get used to was that they had to be very clear about what they wanted from the development organization because there is no slack time. If you want something and you expect to have it done in the next iteration (monthly cycle), you have to be able to state it very clearly or it won’t even get started. It also means that development is very closely connected to the corporate strategy. For every task, developers ask “is this aligned with our overall direction?”

Agile has had a very positive effect on their hiring. Developers like the fact that Agile provides the additional challenge of solving business problems instead of just technical problems which requires thinking at a higher level. Developers at Litle report that they have a higher level of job satisfaction than in previous companies that were not using Agile because they see the results of their software development efforts installed into production every month. Also, they like the fact that there is much less work which amounts to “implement this spec.”

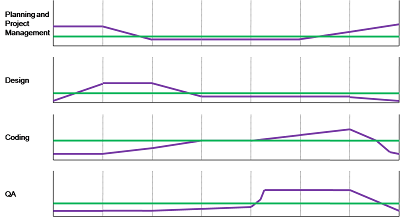

Litle’s software is hosted at multiple off-site datacenters and they upgrade their software every month like clockwork. In reality, they are doing ~7 week iterations which overlap such that they are releasing monthly. The first week of the development cycle is planning, the next four are development, and the final two are production acceptance testing (PAT) and deployment. Each iteration starts on the first Monday of the month. Some iterations are 4 weeks and others are 5 weeks, but there are a total of 12 iterations a year.

Although updating such a mission-critical application might seem risky to do every month, a lot of the perceived risk comes from the typical lack of fully-automated testing. Litle has a very large body of automated tests (over 30,000) and also has a test system which simulates the usage patterns and load of organizations like Visa and Master Card. Every change is subjected to the same sort of testing that typically takes traditional development organizations multiple person years of effort to achieve. As a result, the quality of their monthly upgrades is unusually high even compared to traditional product release cycles of six months to a year or more.

Their development teams are entirely collocated with no offshore or offsite development teams. For each project they assign a team consisting of multiple pair programming teams. Over time they have grown to a development team of 35 including QA and a codebase that contains 50,000 files including test cases and have had to add practices in order to scale XP. The biggest problem they ran into as they have grown was integration of newly developed code into the existing codebase. To address this, in 2007 they added the practice of Multi-Stage Frequent Integration to their implementation of XP. They do frequent integration instead of continuous integration because a full build/test cycle takes 5 hours.

Prior to implementing Multi-Stage Frequent Integration, they would have to manually pore over all build and test failures to determine which change caused which failures. This was done by very senior developers that were familiar with all aspects of the system to be able to understand complex interactions between unrelated components of the system.

Using Multi-Stage Frequent Integration, each project works against their own team branch, merging changes from the mainline into their team branch every day or two, and doing their own build/test/cycle with just that team’s changes.

Thus, any failure must be a result of one of their changes. When the build/test cycle is successful, the team then merges their changes into the mainline. As a result, any team-specific problems are identified and removed prior to mainline integration and the only problems that arise in the mainline are those that are due to interactions between changes from multiple teams. The isolation also simplifies the job of figuring out what changes may have caused a problem because they only have to look at changes made by a single team, not the changes made by all developers.

Tests and code are written in parallel for each work item as that work item is started. They do not distinguish between enhancement requests and defects. All assigned work is tracked in their issue tracking system and all work that developers do is associated with a work item in the issue tracking system. This is done to automate compliance as they need to pass biannual SAS70 Type 2 audits and annual Payment Card Industry (PCI) audits.

The PCI audits go smoothly. According to Dave: “You have to do them yearly, we’ve been doing them for 5 years. We’ve never had a problem. If you’re doing development the right way, you’re not going to have a problem with audits, because all they’re checking is that you follow the best practices of software development. You must use source code control, track why changes are made, ensure that the work done aligns with the company’s goals, and that your app meets data security requirements. On the auditors’ first visit, they said passing it was going to be a big problem because of our size (they figured, ‘small’, meant insufficient), and that we would likely have to make a lot of changes to pass. When the audit was complete--the auditors were surprised. They said they had never seen anyone do this good of a job the first time out.”

Dave also sees their long track record of successful use of Agile as a competitive advantage: “Because we have our monthly releases, our sales people are able to work with our product people to adjust the company priorities for what makes the most sense for the business. Rather than having to pick everything we need to fit in for the year now and then get together again in a year, it becomes a regular monthly meeting where they look at the priorities together. So if there is a vertical we’re not in yet or there’s a vertical that we are trying to expand in or there’s something that makes sense for the business, if we decide as a company we should go after that business, we bid on it.”

More InformationI look forward to any questions about the case study. By the way, if you are an AccuRev user, keep a look out for your invitation to the local user group meeting. David Tarbox will be speaking about his experiences using AccuRev for Agile Development.

In the meantime, you may be interested in learning more about

Litle & Co.,

Multi-Stage Continuous Integration, or

AccuRev.

If you would be interested in participating in an Agile case study for the book, please

contact me.

TOC: Zero to Hyper Agile in 90 Days or Less